Catie McVey Is Helping Cattle Farmers Build More Resilient Cows

November 28, 2023

By Jenna Jablonski

Catie McVey (Cohort 2023, DairyFIT) is from Alamance County, North Carolina, which was once home to over 100 dairies. When McVey left for grad school, only about a dozen Grade-A dairies were left. By the time she graduated and returned home, only one remained.

“Trying to future-proof the dairy world is on everybody's minds,” says McVey. Not only are dairy farmers struggling to hand their farms down to the next generation, but they are also facing unprecedented climate-related challenges, including extreme weather, economic fluctuations, and supply chain uncertainties.

As founder and CEO of the livestock data analytics company DairyFIT, McVey is determined to build more resilient cows that can withstand the volatility of climate change, and in turn, unlock greener farming practices. After all, McVey says, what’s good for cows tends to be what’s good for the planet.

“Cow welfare and farmer welfare are inextricably linked... A happy cow is a healthy cow is a productive and profitable cow. ”

McVey compares today’s dairy cows to Ferraris—they are high-value, high-performance machines in terms of their extraordinary milk production capabilities, but they lack durability. “What we need now are more Subaru cows,” she says.

McVey explains that dairy cows have been bred for high production. “It’s easy to measure because it’s how people get paid,” she says. “The health and the resiliency traits are fundamentally more challenging to quantify, but they're just as important.”

With DairyFIT, McVey is on a mission to balance the health + resilience + production equation.

.png)

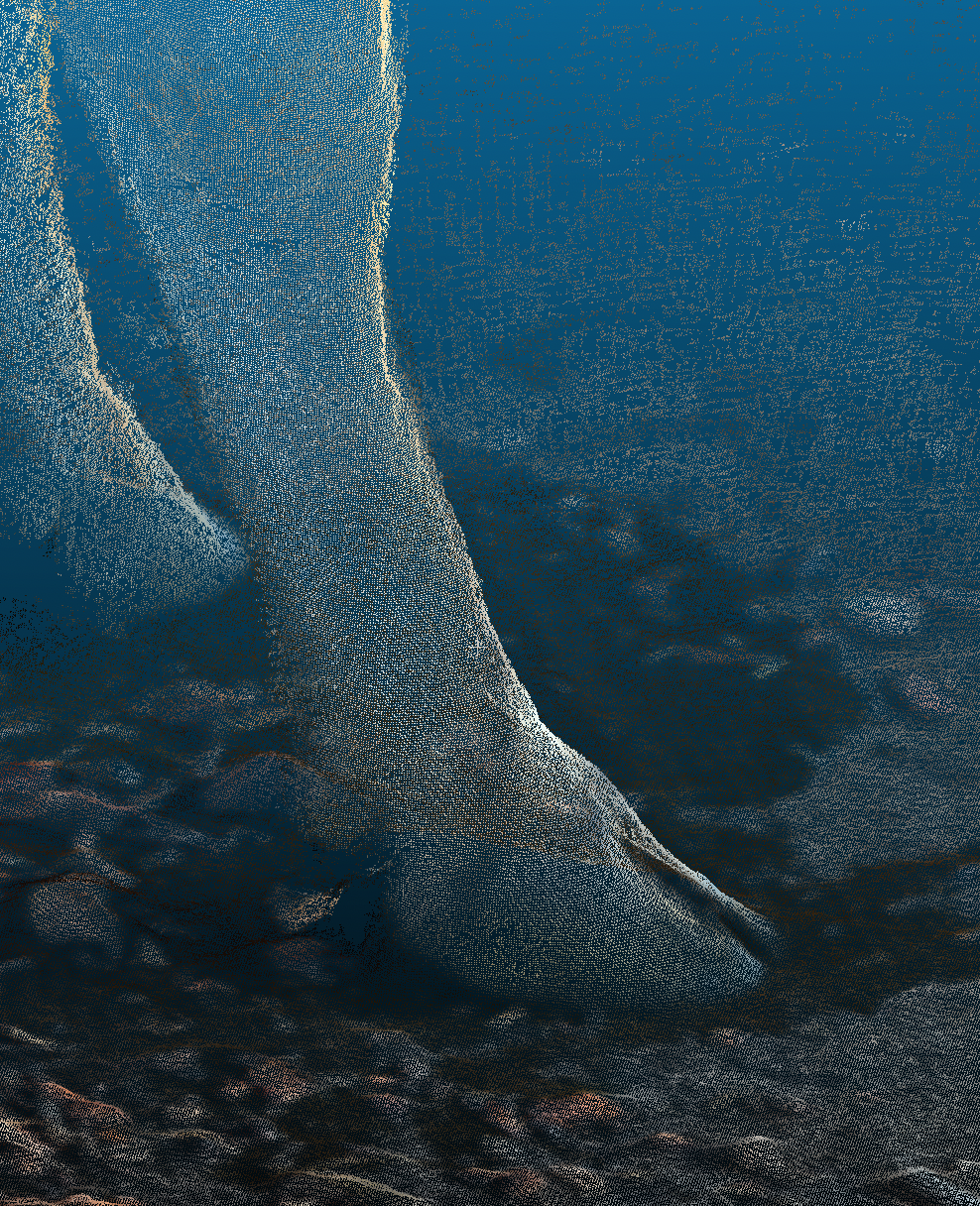

DairyFIT’s technology relies on high-accuracy 3D images, such as this hoof scan taken by McVey. It then uses geometric projection algorithms to distill all the information in the image into a handful of descriptive 1D morphometric values, such as toe length, which affects gait breakover and torque on the leg joints, and straightness of the toe, which affects the balance of heel-toe weight distribution. (Image courtesy of Catie McVey/DairyFIT)

DairyFIT provides farmers with insights in all three of these areas that were previously difficult to measure. By scanning a cow’s physical features, such as its face or feet, DairyFIT’s patented computer vision and machine-learning technology can detect morphological indicators of how genetically well-equipped a cow is to cope with stressors in its environment and stay free of injury and disease. Farmers can then use these insights to support the day-to-day management of their herds, and in the longer term, to inform breeding decisions.

McVey emphasizes that her technology is not just for big farms. By running DairyFIT’s 3D scanning technology through a user-friendly iPhone application, McVey hopes it will be “just as accessible for a 20-cow herd as it is for a 10,000-cow herd.” The app—which is edge-enabled, or able to process data at the source—is in development now, with a beta on the way in 2024.

For big and small farms alike, a potentially revolutionary impact of DairyFIT’s technology is the precision management of dairy cows. “We have all these preventative health tools, but if you take a whole-herd approach and give them to every single cow, that gets really expensive, really fast,” McVey explains. “So the lofty goal is being able to read these physical indicators to tell me, ‘Okay, this cow’s a no-drama mamma, she'll just keep trucking’ or, ‘This is my potential milk dud cow. I need to hold her hand and give her some extra help.’”

McVey believes that building better cows will ultimately save more farms from shuttering. “Cow welfare and farmer welfare are inextricably linked,” says McVey. “The longevity and resiliency of a cow are integrally linked to the longevity and resiliency of the dairy itself, both economically and logistically. A happy cow is a healthy cow is a productive and profitable cow—it’s hard to get around that maxim.”

Unlocking regenerative agriculture

After completing her Ph.D. at UC Davis, McVey moved back home to North Carolina. Despite the local dairy industry not being what it used to be, McVey was attracted to the state’s rich ecosystem of small farms and innovative regenerative agriculture, which implements methods such as rotational, high-density grazing, the planting of cover crops, and reduced plowing to improve soil health.

Regenerative agriculture is a movement McVey is excited and hopeful about. “It creates a low-input, low-impact type of farm that's more resilient to supply chain issues, economic fluctuations, and climate impacts,” she says. Further, it allows farmland to function as a carbon sink, as healthy soil that’s rich in organic matter traps more atmospheric carbon.

While this method of farming is growing in popularity, especially among smaller farms, it requires more rugged cows, McVey points out. So, what makes a successful regenerative cow? McVey rattles off a long list of features: You have to be able to move her every day, so she needs good feet and a good temperament. She needs a good mouth and a big belly to collect and ferment grass. She needs to have a calf easily with no complications. She needs good udders for milk production.

“Almost all those traits have been challenging to objectively measure before DairyFIT,” says McVey.

Why cows?

McVey’s technology is deeply rooted in her upbringing in the foothills of North Carolina, a traditional dairy farming region.

Her grandfather grew up on the family dairy farm but transitioned to real estate appraisal and then engineering after the local dairy industry began to decline. “In the 50s, 60s, and 70s, lots of farms went under and it was really, really rough,” says McVey. “So much so that people were stapling notes with the suicide hotline number to the back of milk checks.”

Given this regional history, McVey wasn’t exactly encouraged to pursue anything related to agriculture. “The message that ‘if you want opportunities and options, you need to get out’ was still prevalent when I was growing up,” she says. It was not until later that she realized, “There is actually a lot of opportunity in agriculture, especially when you bring technology into it.”

DairyFIT can be traced back to McVey’s long-held obsession with “old cowboy adages” about how animals’ physical features can predict their health and temperaments. She was fascinated by this old-timey wisdom she had grown up around, and she decided to see if she could use science to back it up. This research question became the basis of a project that landed her at the International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) as a sophomore in high school.

After attending one of the poorest high schools in the state, McVey transferred to one of the top ten high schools in the country: the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics (NCSSM), a public, residential STEM high school. Despite never having done anything more with a computer than word processing and web surfing, her computational chemistry instructor sensed her aptitude for computer science. “You are one of the most stubborn rednecks I've ever met in my life,” she remembers him telling her. “You will be fantastic at coding.”

McVey competed at the International Science and Engineering Fair for the first time as a sophomore in high school with a project investigating the link between animals’ facial features and their temperaments. (Image courtesy of Catie McVey)

McVey continued digging into “old cowboy adages,” now from a data science angle, as her independent research project at NCSSM. Paired with an amazing mentor who she describes as “a Yale patent lawyer turned OG data scientist at Duke,” she ultimately became an early innovator at the intersection of computer vision and statistics. She returned to ISEF as a senior, this time winning a specialty award from the U.S. Air Force. By the time she finished high school, she had filed for five patents related to the facial inference technology she had developed, which could infer properties from images of animals.

The path to DairyFIT

McVey deepened her research on facial morphometrics, or using the shape of facial features to infer traits related to hormonal balance, during grad school at Colorado State University, where she earned dual master’s degrees in applied statistics and livestock systems. She furthered this research during her Ph.D. in animal biology at UC Davis but was limited in her access to data collection due to the pandemic. Instead, she leaned into developing the machine-learning dimension of her technology, exploring the questions: What makes a resilient cow? How do you quantify that? How can you mine that from information that already exists on a farm?

While in California, McVey also had the challenging but edifying experience of living through two brutal fire seasons. “I was in the Valley for both of the summers when it was literally raining ash from the sky and there was no sunshine for weeks on end,” she says. “I grew up in a Baptist church—I cannot just ignore ash falling from the sky!” McVey also saw firsthand the impact of the climate crisis on agriculture. “The cows are coughing and you can't get them to eat because there's literally ash falling on their food,” she says. “It definitely incentivized me to want to get onto the frontlines of fighting for farmers.”

This urgency influenced McVey’s decision to pursue entrepreneurship over academia. Despite her strong support for the land-grant mission, she was discouraged by the funding landscape, especially for projects in agriculture. “The size of our grants has not really evolved to reflect the complexity of the problems that we need to work on these days,” she says, which also impacts the pace of innovation. Land-grant universities are working on solutions that might be deployed ten years down the road, for example. “And I'm like, there are a lot of problems we need to solve this year,” says McVey.

McVey prototyped scanning devices at Reverence Farms in Graham, NC this past summer. She started with Intel RealSense LiDAR depth cameras and has since iterated to a less cumbersome iPhone-based scanning system. (Image courtesy of Catie McVey)

Since launching DairyFIT in September 2022 and starting the Activate Fellowship in June 2023, McVey has focused on customer discovery and made some pivots based on what she’s learned. Despite originally focusing on cows’ faces, she’s heard over and over again about unreliable feet as a pain point for farmers. In an effort to meet farmers’ most immediate needs, the first beta version of DairyFIT’s technology will analyze cows’ feet. She still plans to map various other phenotypes (or observable characteristics) and is currently writing a Small Business Innovation Research grant application in hopes of receiving federal funding to develop DairyFIT’s face-focused technology.

Getting back to her roots

Being a fellow in the Activate Anywhere Community has allowed McVey to run her business from North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park (RTP), where she is close to family, and to the entrepreneurial and farming communities that make the most sense for her business.

“Everybody thought I was crazy, launching a startup and leaving California,” she says. But RTP is a thriving hub for biotech and ag tech, with many resources to support first-time entrepreneurs. Plus, she’s surrounded by women founders—something she did not find in the California startup scene.

Additionally, she is embedded in an agricultural community that provides valuable insights for DairyFIT. “I feel like almost all farmers I work with are smarter than me,” she says. “I learn a lot from them, particularly the folks with the smaller herds that have that intimate connection with their cows.”

McVey is not only innovating a more secure future for agriculture, she is living out this vision as she restores a piece of her family’s homestead in Graham, NC. “We've taken care of our little 45 acres for six generations. The number of small farms that won’t be passed on over the next 10 years—left abandoned or neglected, or bulldozed and developed—is kind of terrifying,” she says. “So being able to attract more young people into this lifestyle with easier-to-care-for, more resilient cows is going to be really important here real soon.”